Crossmodal plasticity of sensory cortical processing

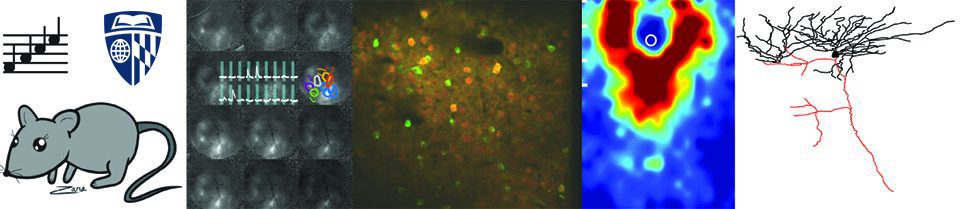

It might not be a surprise that sensory systems do not work in isolation. Moreover, it is well known that visual deprivation (such as blindness) can lead to improved auditory abilities. However the underlying mechanisms that contribute to these “supernormal” abilities are largely unknown. For example it could be that neurons in the visual cortex are recruited to subserve auditory processing, or that neurons in the auditory cortex become better in processing sounds, or some combination of these two mechanisms. Many studies have investigated changes in the visual cortex in long-term blindness and found crossmodal activation of the visually deprived visual cortex (for example by braille reading). We are interested in investigating what happens to other cortical areas in particular the auditory cortex when visual experience is altered for just a short period at older ages. We are looking at how auditory processing and micro-circuits are altered. Our results so far show that brief visual deprivations (simulated blindness) alter auditory processing in that neurons have better frequency discrimination abilities and lower thresholds. Moreover we find that thalamocortical synapses in auditory cortex are strengthened (Petrus et al Neuron 2014, see F1000 review, BBC, NPR, Washington Post, Nature.com, Voice of America). These changes do not only occur on the level of single neurons, but also on the network level. Our in vivo studies show that responses decorrelate and that the frequency preference of auditory cortex neurons is shifted to high or low frequencies (Solarana et al. eNeuro 2019).

Thus some of the changes seen in auditory performance are likely due to changes in the auditory cortex. Seeing changes in thalamocortical connections is quite surprising as our visual deprivations occur after the critical period and indicate that crossmodal influence seem to be more powerful than unimodal influences in changing cortical circuits. We also find extensive changes in intracortical connections (Petrus et al. 2015, Meng et al. 2015, Meng et al. 2017) indicating that visual deprivation has a powerful influence on the auditory cortex. These results raise the question how the lack of vision is signaled to the auditory cortex and how one would might make such changes permanent.

The fact that the frequency preference of auditory cortex neurons is shifted (Solarana et al. eNeuro 2019) suggests to us that maybe the auditory cortex reorganizes to better detect behaviorally important sounds in the dark.

Clinical relevance:

While it is too premature to speculate if this would work in humans (or if humans would even do this) our results give us hope that there might be the potential for simple treatments for human central hearing problems. Moreover, if this works in humans our findings might help to improve hearing in deaf people. Many people are trying to recover their hearing by cochlear implants. These devices work very well in younger children, who recover perfectly. But older individuals who are completely deaf have a difficult time recovering their hearing with these devices. So maybe one can modify training regimes for cochlear implant users to coax the brain to be more plastic and improve their sound processing with cochlear implants.

We are collaborating in this project closely with the lab of Dr. Hey-Kyoung Lee at JHU.